United States Airport Rates and Charges Regulations

(March 15, 2015 by Dafang Wu; PDF version)

This article discusses airport rates and charges regulations in the United States, examines the 2013 FAA Rates and Charges Policy, and reviews large-hub airport ratemaking as of March 2015.

U.S. airports can set airline rates and charges through bilateral agreements or unilateral rate resolutions or ordinances after airline consultation. Federal regulations provide guidance on setting airline rates and charges, and are largely incorporated in Title 49 U.S. Code (USC), enacted by the legislative branch, and Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), established by the administrative branch. Many legal cases ruled by U.S. courts and administrative cases ruled by the Department of Transportation (DOT) helped clarify contents in Title 49 USC and 14 CFR. Although some federal regulations do not extend to bilateral agreements, which are contractual obligations, those regulations have shaped the negotiation landscape between airports and airlines.

Two principles form the foundation of airline rates and charges regulations in the United States: reasonableness, and without unjust discrimination.

Overview of Rates and Charges Methodology

Airline rates and charges methodology can be classified as residual or compensatory. The airport industry has created the third category, hybrid, in the last decade. In Airport Compliance Manual – Order 5090.6B, Chapter 18, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) provides definitions as follows:

- Residual. Agreements that permit aeronautical users to receive a cross-credit of nonaeronautical revenues are generally referred to as residual agreements. In a residual agreement, the airport applies excess nonaeronautical revenue to the airfield costs to reduce air carrier fees; in exchange, the air carriers agree to cover any shortfalls if the nonaeronautical revenue is insufficient to cover airport costs. In a residual agreement, aeronautical users may assume part or all of the liability for nonaeronautical costs. A sponsor may cross-credit nonaeronautical revenues to aeronautical users even in the absence of an agreement. However, except by agreement, a sponsor may not require aeronautical users to cover losses generated by nonaeronautical facilities. A residual rate structure may be accomplished only through agreement of the users.

- Compensatory. An agreement is one in which a sponsor assumes all liability for airport costs and retains all airport revenue for its own use in accordance with federal requirements. Aeronautical users are charged only for the costs of the aeronautical facilities they use.

- Hybrid. Sponsors frequently adopt rate-setting systems that employ elements of both residual and compensatory approaches. Such agreements may charge aeronautical users for the use of aeronautical facilities with aeronautical users assuming additional responsibility for airport costs in return for a share of nonaeronautical revenues that offset aeronautical costs.

A hybrid ratemaking methodology should be a subset of residual ratemaking methodologies. A compensatory ratemaking methodology without a residual protection should not be classified as hybrid.

Additional note by DWU AI on 2/17/2026: Based on popular demand within the industry, the hybrid category is now commonly split into two subcategories: hybrid residual and hybrid compensatory. A hybrid residual methodology provides airlines with revenue sharing credits AND includes Extraordinary Coverage Protection (ECP) — a residual safety net requiring airlines to pay additional amounts when the rate covenant is not met. Airlines bear the risk. A hybrid compensatory methodology provides airlines with revenue sharing credits but does NOT include ECP — the airport bears the risk for areas outside defined airline cost centers. The distinguishing feature is the presence or absence of ECP. The four-category spectrum is therefore: Residual → Hybrid Residual → Hybrid Compensatory → Compensatory.

Prohibition of Imposing Residual Ratemaking

As the FAA emphasizes in the compliance manual, as well as in 2013 Policy Regarding Airport Rates and Charges (the 2013 Rate Policy), an airport sponsor cannot impose residual ratemaking upon airlines and must obtain the residual guarantee through a bilateral agreement. This clause has far-reaching implications – prohibiting airports from shifting financial risks to airlines without airline consent, and encouraging airports to plan prudently when taking additional risks.

If airlines are not supporting an airport in taking additional risks, typically in the form of undertaking a large capital project, the airport has two major options: (a) impose rates unilaterally after a careful affordability study and proceed with the capital project, or (b) revise the scope of the capital project and/or continue negotiating with the airlines. If, through the affordability study, the airport concludes that estimated airlines rates and charges, together with other nonaeronautical revenues, are not adequate to pay all obligations, the airport must revise the scope or return to the negotiation table.

When airports and airlines cannot reach a consensus during an airline agreement negotiation, imposing airline rates and charges unilaterally usually disrupts the airline relationship for the years to follow. The FAA states in the opening sentence of the 2013 Rate Policy that, “It is the fundamental position of the Department that the issue of rates and charges is best addressed at the local level by agreement between users and airports.” Nevertheless, understanding airline rates and charges under unilateral ratemaking gives airport management a clear understanding of its leverage, and can usually guide the negotiation to reach an agreement satisfactory to both airports and airlines.

Federal Regulations Regarding Airport Rates and Charges

49 USC 40116 originates from the 1973 Anti-Head Tax Act, and prohibits “unreasonable burden and discriminate” but allows “reasonable rental charges, landing fees, and other service charges from aircraft operators for using airport facilities of an airport owned or operated by that State or subdivision.” The term “reasonable” is open to interpretation.

49 USC 47107 sets certain conditions that an airport sponsor must agree to when receiving federal grants. The FAA eventually developed a document referred to as the grant assurance, which becomes a contractual obligation between the airports and the FAA. Since a majority of U.S. airports, if not all, have received federal grants under the Airport Improvement Program, the grant assurance is one of the most important documents on airport rates and charges. The grant assurance reiterated the requirements in 49 USC 47107 that the airport must “be available for public use on reasonable conditions and without unjust discrimination.” The grant assurance also incorporates other rules and policies, such as the 1999 Revenue Use Policy, which prohibits an airport sponsor from using airport revenues outside the airport, except for limited exceptions. The FAA published a clarification in November 2014 that aviation fuel taxes are subject to the revenue use policy, which caused some major issues for smaller airports.

49 USC 47129 requires the Secretary of the Department of Transportation (DOT) to determine whether an airport fee is reasonable or not, and to set out a procedure to resolve airport-airline disputes regarding airport fees. Accordingly, the DOT developed a rates and charges policy (discussed below), and established a procedure, codified as 14 CFR Part 302, with subpart F applied to airport fees. This procedure does not apply to any dispute related to bilateral agreements. Among others, the procedure requires an airport sponsor to respond within 14 days and to set forth the answering party’s entire response.

FAA Rates and Charges Policy

The FAA developed an interim policy in 1995, as required by Congress in 1994, and finalized the policy in June 1996 (the 1996 Rate Policy). The FAA discussed at length supplemental information regarding the details of rates and charges considerations, many of which still have reference value today. However, the 1996 Rate Policy was quickly challenged by airlines, and a major portion was vacated in August 1997. Among other issues, the 1996 Rate Policy requires airports to use the historical cost approach in setting airfield fees, and to use any reasonable methods in setting other aeronautical fees. The court of appeals considered this approach arbitrary and capricious.

In September 2013, the FAA published the 2013 Policy Regarding Airport Rates and Charges (the 2013 Rate Policy), reflecting all additions and deletions since the 1996 Rate Policy.

- The 2013 Rate Policy reiterated that “It is the fundamental position of the Department that the issue of rates and charges is best addressed at the local level by agreement between users and airports” and the principles of

- Self-compliance

- Rates that are “fair and reasonable”

- No unjust discrimination

- Financial self-sufficiency

- No revenue diversion

- Same principles applying to international operations

- The 2013 Rate Policy defines aeronautical use as “any activity that involves, makes possible, is required for the safety of, or is otherwise directly related to, the operation of aircraft,” which “includes services provided by air carriers related directly and substantially to the movement of passengers, baggage, mail and cargo on the airport.”

- Compensatory, residual, or hybrid ratemaking are all permitted, although residual ratemaking cannot be imposed without airline consent.

- When evaluating “fair and reasonable,” the FAA has further provided the following:

- Airfield fees shall not exceed airfield costs, unless agreed to by aeronautical users.

- Total costs may include a reasonable amount for debt service coverage and reserves, and may include costs for reliever airports.

- Allocation of total costs must be reasonable, and transparent, without unjust discrimination.

- Although airport operators are prohibited from engaging in unjust discrimination, the following are permitted, among others

- Difference based on signatory vs. nonsignatory carrier

- Peak pricing system

Legal Cases and Administrative Cases

Dozens of legal cases and administrative cases have put the FAA’s interpretation to the test, and continue to affect airport sponsors when they determine how to set airline rates and charges on a unilateral basis. Selected legal cases are as follows:

- 1972 Evansville. The U.S. Supreme Court determined that an airport charge is valid because it reflects “a fair, if imperfect, approximation of use of facilities for whose benefits they are imposing,” and is neither discriminatory nor excessive.

- 1994 County of Kent. The Supreme Court rejected the airline's notion that it should take into account concession revenues when deciding whether airline rates are reasonable.

Selected DOT rulings are as follows:

- 1995 LAX I and 1997 LAX II. The DOT concluded that the City of Los Angeles’ landing fee, which was based on fair market value, was unreasonable. In addition,

- The DOT found that an airport should have the ability to include imputed interest on its aeronautical investments, to the extent that such investments were not recovered from the prior rate base.

- The DOT found that an airport can allocate a share of roadway costs to the airfield cost center and does NOT need to credit a share of its nonaeronautical revenues in doing so.

- 1996 MIA. The DOT concluded that the equalized terminal rental rate was reasonable, because the Dade County argued “each airline will at some time have the advantage of operating from the newest and most modem facilities in the terminal.” Air Canada sued the DOT in 1997, and the case was eventually settled in 2000.

- 2007 LAX III. The airlines argued that using rentable space as a denominator to calculate the terminal rental rate, or using fair market value, was unreasonable and discriminatory. The DOT concluded, among other things, that (a) the cost allocation process for M&O expenses was reasonable, (b) using rentable space instead of usable space, in general, was reasonable, although not in the particular case of LAX, and (c) a fee methodology designed to capture costs using a compensatory method was generally reasonable.

The most recent case is United Airlines vs. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey regarding ratemaking at Newark International Airport. This case is ongoing as of March 2015, and the docket can be found at this link.

Summary of Potentially Acceptable Practices in Unilateral Rate-Setting

Airport sponsors are encouraged to consult their rates and charges counsel, because interpretation of general principles – reasonable and without unjust discrimination – will be continuously tested by future rate disputes. Some potentially acceptable practices when setting rates unilaterally are as follows:

- General ratemaking approach. It has been made clear that compensatory ratemaking is acceptable, although the exact application of this methodology is still being examined

- Total costs.

- The DOT mentioned that debt service coverage, cash reserves to protect against operation risk, cash reserves for other contingencies, and reliever airport costs could be added to the airline rate base.

- Although not clarified by the DOT, pension obligations have been widely added to the airline rate base because those payments are typically cash outlays. Funding for other post-employment benefits (OPEB) is less certain, especially when there is no trust fund established for OPEB.

- Using the historical cost seems to be the only acceptable approach for setting airfield fees after the LAX I and II rulings. The DOT made it clear that using fair market value for the terminal building is acceptable, although the opportunity cost has to be evaluated under the context of grant assurance.

- Allocation of total costs to cost centers. The allocation has to be reasonable, transparent and not unjustly discriminatory. As mentioned in the 1972 Evansville case, the allocation can be an approximation rather than a perfect allocation.

- Although not confirmed by the DOT, a majority of U.S. airports are using residual ratemaking for airfield cost centers, after crediting revenues collected from other airfield users.

- Using rentable space as denominator of the terminal rental rate calculation is reasonable. However, there haave not yet been legal cases on how to exactly determine rentable space vs. nonrentable space

Review of Large-Hub Airports Ratemaking

Although the DOT stated that “practices of other airports are not necessarily decisive for reasonableness determinations,” it is nevertheless beneficial to understand how other airports set rates and charges.

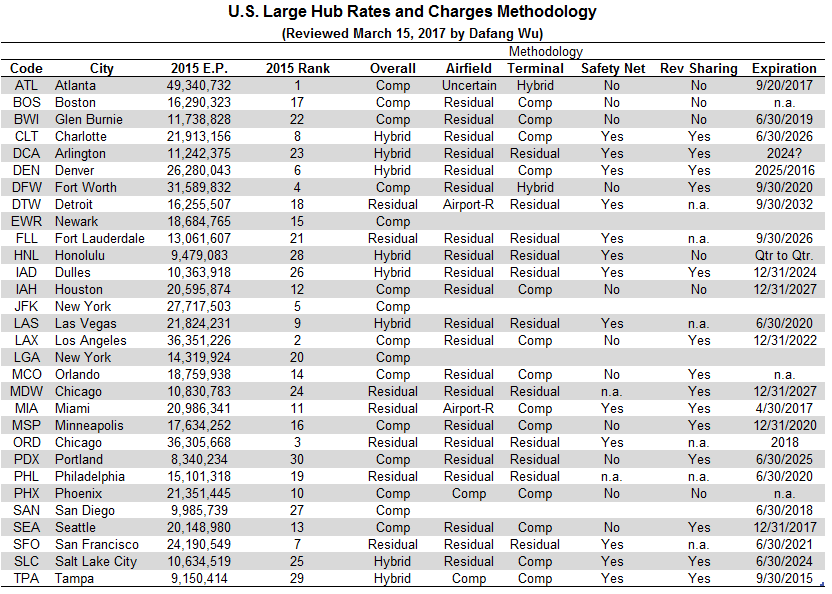

As shown in the following table, 16 airports out of a total of 30 large-hub airports are employing compensatory ratemaking methodologies as of March 2015, while 8 airports have residual ratemaking methodologies and 6 airports use a hybrid approach. The classification of the ratemaking methodology in this table is different from the FAA classification:

- Residual ratemaking has the same definition as in the FAA compliance manual

- For an airport to have hybrid ratemaking in this table, it must have received extraordinary coverage protection (ECP) from airlines, which is a residual safety net, requiring airlines to pay an extra amount when the rate covenant is not met.

- Other airports, although providing voluntary credit to airline rates and charges, have not received ECP from airlines, and are listed as compensatory

- BOS and PHX are two airports setting rates by ordinance, without airline agreements. It is unclear how the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey sets airline rates.

- All other airports have airline agreements, or both rate ordinance and rate agreements.

Ratemaking methodologies at large-hub airports continue to shift from residual to hybrid or compensatory. However, instead of setting rates by ordinance, more airports, such as LAX, MCO and SEA, are adopting a combination of rate ordinance and rate agreement. In this structure,

- An airport sponsor establishes a rate ordinance, allowing setting rates unilaterally. This is typically due to inability to reach a satisfactory airline agreement toward a major capital investment.

- At the same time, the airport sponsor distributes rate agreements, allowing airlines to sign up as signatory airlines and enjoy revenue sharing on the condition that such airlines will not sue the sponsor for the rate ordinance

This trend may not be true for medium-hub or small-hub airports, which are struggling to develop additional air service when U.S. airlines continue to practice capacity control and route optimization. Smaller airports are more susceptible to retaliation acts when attempting to impose an airline rate unilaterally to increase revenues, unlike large-hub airports, which have relatively more power at airline agreement negotiation tables.